by Abhishek Kumar, Saskia Reimann, Pari Abbasli

Header video by innerjalz

It’s been three months since Iranian citizens, mostly women, have been fighting for their rights and freedoms in the streets against the brutal security forces of the current Iranian regime. “Woman, life, freedom (Zan, Zendegi, Azadi)” is one of their most important slogans to expand a global action in solidarity with Iranian women and girls who are courageously demonstrating peacefully for their fundamental human rights.

Looking at the current Iranian protests, one would feel that the protests are just about the denial of women’s rights by the Iranian regime. But, what is interesting to know here is that these protests are not just about gender equality in Iran but an all encompassing continuation of the anti-regime protests that began in the country in 2017.

The findings of a study on ‘Art during the Black Lives Matter movement’, published by Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, emotional expressions, psychology of protests comprise both explicit messages and complex feelings that require dedicated spaces of expression of more vulnerable emotions.

The study of 638 phrases and 110 images shows that artworks during the Black Lives Matter protests expressed anger, demand for social justice and pride. Artists showing their support to the protestors by visualizing their rage on their artworks more than sadness and grief. The art pieces also represented a social identity.

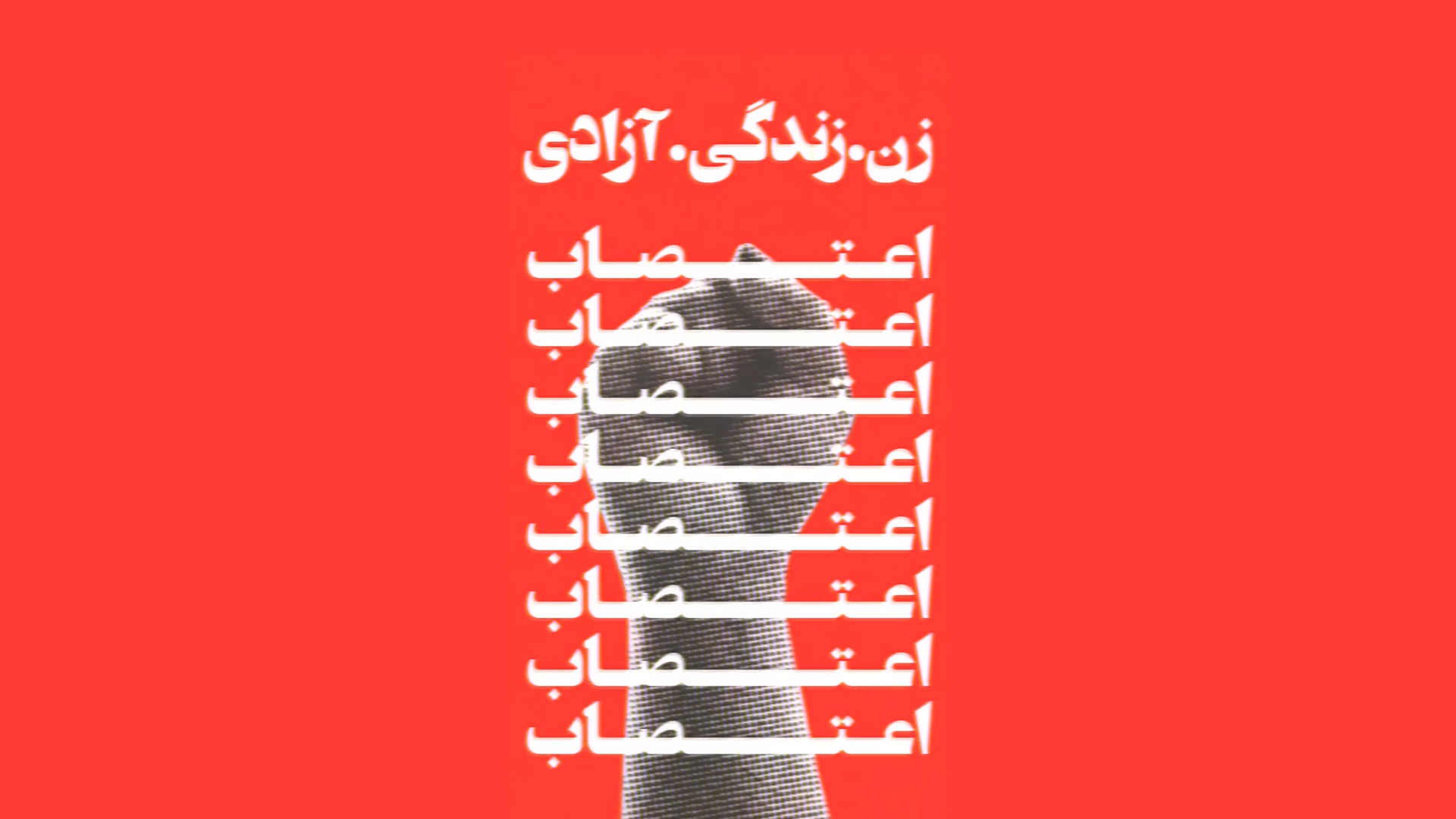

Similarly, in the ongoing Iranian protests, we can suppose that the underlying emotion in the artworks is a deep sense of anger, pain and frustration felt by the artists against a hardline regime which constantly denies the basic rights of freedom.

Books not guns, culture not violence

Dreamers (2003), Dir. Bernardo Bertolucci

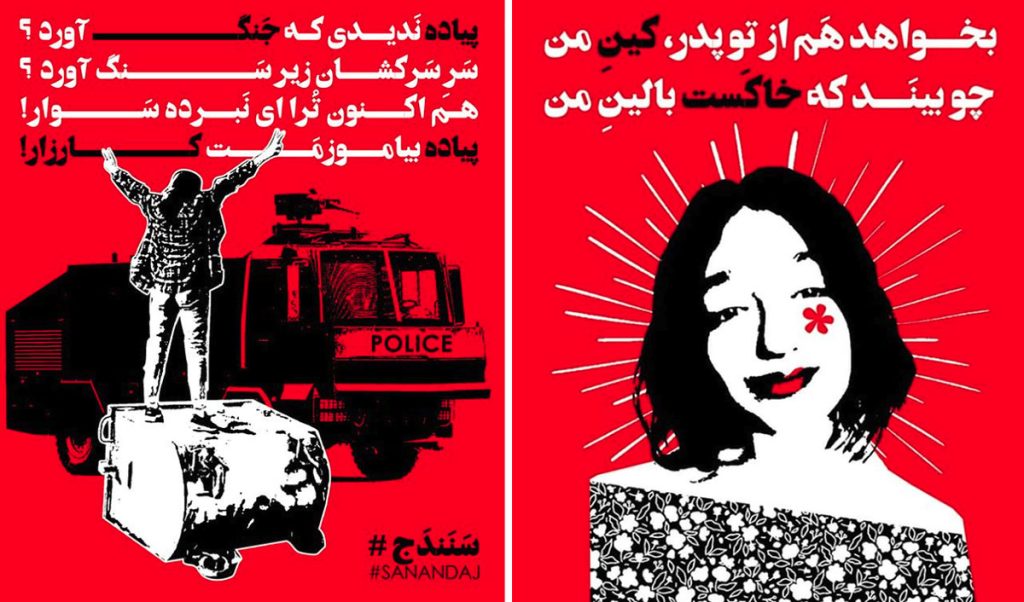

Iranian artists who want to be the voice of the young people tortured in prison, the struggle of unarmed citizens, use their pens, brushes and instruments to inflame the resistance in the streets.

The art forms on social media in the wake of the current protests that began in September this year appear more directly liberally employing the colors of red, black and white to convey seriousness as compared with indirect visual language which was a hallmark of earlier protest art. Meysam Azarzad is one of the leading artists during the protests. He vizualized the uprising of people, mourning for the people who got killed in the protests, young people who faced arrest because of the fighting against the regime, with the stylistic of combination of these three colors.

Adeena Hasan, a Bangladeshi visual artist, said in her interview to Her zindagi that art holds a special place in protest culture as it has the ability to seamlessly transcend language barriers and cultural differences: “Bright colors roar for attention, while duller tones can highlight the severity of suffering by igniting compassion among the masses.”

We wanted to find out to what extent art can be seen as a soft power in the current protests. Our interviewee Marie Rask Bjerre Odgaard cand. scient. antropologi, Ph.D. student from Aarhus University told us that art has historically (not only in the region but globally) always had a central role in voicing both moral, political and cultural concerns, as a way as documenting moral change:

In times of social upheaval – or in this case of large scale protest – artists can serve as both documenters and amplifiers of such protests, but their aesthetic engagements at times also spark affective dimensions of feelings of sharedness in emerging counterpublics

Marie Rask Bjerre Odgaard

In our specific case, expressing solidarity with the protesters also poses challenges for the artists. Ms Odgaard pointed out that art can be traced back to the artist and that this can lead to consequences for the artist. Another problem is that artworks can be removed from their original meaning, especially “social media gives a different affective dimension to the works when they are distributed far and wide” but this is a general problem with social media.

Iranian pop art community on Instagram has important pieces about the protest called “For Freedom” by illustrator, motion graphic designer Elham Azar.

With this illustrative work, in fact, we see the nuances of women tearing, burning, throwing and crushing their hijabs in protests. These actions, which add strength to Iranian protests, are currently one of the steps that determine the future of Iran.

The general approach of the secular part of the society against the compulsory hijab plays a very important role here. The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change shows that 71 percent of males and 74 per cent of females disagree with the mandatory imposition of the hijab. As the data contains the similar positions of males and females about hijabs, protests break the misogynistic prescriptions of the regime.

Dancing freely for Iranian women

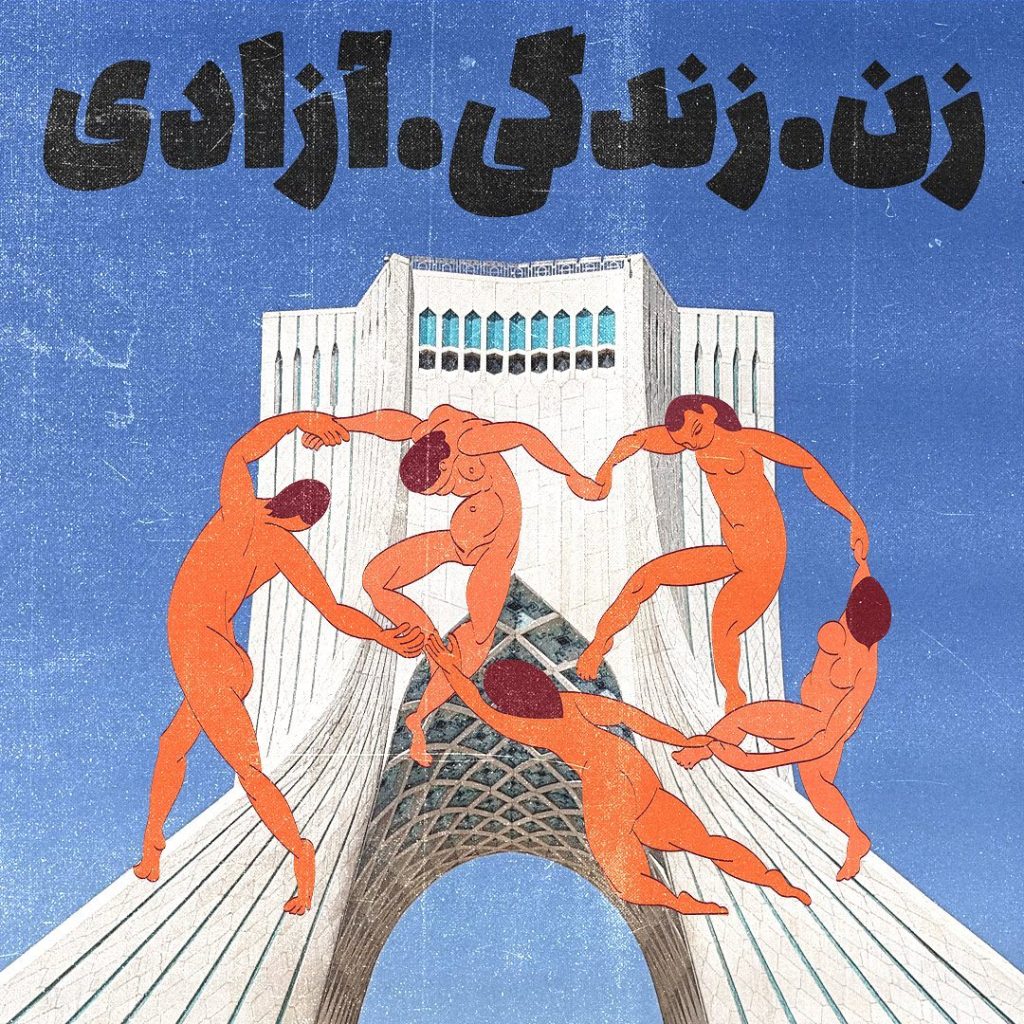

As Iranian women are prohibited from dancing and singing, some local artists documenting the revolutionary actions of Iranian women on the streets, protesting for their freedoms. Contextually for the expressing the support to the women, the Iranian graphic designer Jalz, one of the influential artists on social media created this reknowned digital artwork:

Combining vintage collage art with traditional and new art formats, Jalz began using his art as a voice for the protesters. His most popular poster – collage art of the dancing women from Henry Matisse’s “La Danse” (1910) on top of Iran’s well known Freedom Square with the slogan “زن آزادی زندگی (Woman, Life, Freedom)”.

Maybe my country will be free at the time you publish your article

– Farah Ahmadi

Iranian-Azerbaijani art critic and artist Farah Ahmadi* (name changed) said that Iran went backwards in many issues after the 1979 revolution: “But art was the only sphere that developed in Iran and reached incredible levels. The spread of this development among people was also manifested in protests because people are in direct contact with art.”

Farah is very hopeful that Iranian art will develop if the protests reach some results. She mentioned the following about the current situation of her artist friends: “Unfortunately, many of my artist friends were detained and arrested by state authorities. Many have reduced their artistic activity to zero because they are either arrested or in shock of the events happening in Iran. It is not easy to create a work of art in Iran at the moment. If this revolution takes place, a new century will begin to emerge in Iranian art.”

Iranian, Toronto-based writer, poet, photographer and filmmaker Golshan Abdmoulaie mentioned about the government’s action against art and artists: “The Islamic government fears artists, that’s why many of them are in prison. It’s important to talk about this. Censorship and punishment is a driving force of the Islamic government to silence artists.”

Protests, literature and cinema

Claus Valling Pedersen, lecturer from the Department of Intercultural and Regional Studies from the University of Copenhagen, stressed that “literature, but also in film had been a way of communicating protest out – in spite of the censorship, quite heavy after the 1979 revolution and before. So you’ve always seen political and social and economical criticism in literature and film. I dont think it’s a special role just now, during the protests, they have been very vocal about the actors, filmmakers and writers during the last couple of months.”

He cannot judge whether the art world has really changed, because “surely there will be changes” like writers and filmmakers who will not respond to censorship “but I have not seen any changing artistic expression, because I’m not there and nothing comes out of Iran now. At the end of the day, we are 5000 kilometers away and the internet is almost shut down all the time.”

Dariush Zare* (name changed) studied architecture in Iran before moving to Europe to pursue film history. He is currently doing a Master’s Degree at a renowned university. His focus is the history of Iran’s “Free Cinema” from the 1950s until today.

According to Dariush, art plays an important role in these protests because the art that makes it out of Iran and into the world speaks a universal language. At the same time, art is a way for the artist to show the voice from Iran and support the revolt:

In this case to show the reality very clearly, very easy, very fast, very understanding and very sentimental

Dariush Zare

Centre Pompidou, Paris, one of the most important contemporary art spaces in the world. Here, on 15 October 2022, almost exactly one month after the death of Mahsa Amini, a performance by the two Iranian artists Niyaz Azadikhah and Alireza Shojaian took place. Suture sur le corps de la liberté – stitches on the body of freedom – was meant to create a space to express solitariness with Iran. The week before, visitors were invited to leave a piece of hair in front of the building. On 15 October, the two artists silently sewed the probably most spoken slogan “Femme, vie, liberté” with hair into a white cloth with a red thread. The performance was repeated at the end of November at the Imago Mundi Foundation in Treviso. This time the words “Donna, vita, libertà” were sewn in with hair and red thread. Even if the language changes, the message remains the same.

Dariush mentioned that after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the Iranian cinema was one of the first “Islamised” cinemas. To be precise, this means that the actresses had to start wearing a hijab, whether in the film or at film festivals, even if they have been abroad like at the Berlinale in Berlin. Katayoun Riahi, a well-known actress, took off her hijab online after the first protests of Mahsa Amini. She was followed by the world-famous actress Taraneh Alidoosti: “So this is very important in the field of art rights as well as social policy and all that.”

Sound of the fight against pressure

Farah Ahmadi said that many artists, including herself, were inspired to create more emotional works because of the protests: “Protests in Iran have a strong impact on artists and the art sphere. In particular, it leads to the creation of dramatic, emotional works in many fields, including the field of music. Because the protests are terrible – people are dying and can’t even get their basic rights.”

As the sense of sadness of Iranian music is mostly remarkable, during the protests the faith, hope and power of people lead musicians to create sadder pieces in music.

In 2023, the Grammys will recognize a new merit award: best song for social change. Recently, this new award captured national attention when over a hundred thousand submissions came in for one song. For example, “Baraye” by the Iranian composer Shervin Hajipour.

Hajipour published “Baraye…” (Persian: برای, For…; Because of…) on social media which he used tweets about protests starting with the word Baraye…, written in support of the protests. “Baraye…” is considered as an unofficial anthem of the protests.

After his arrest, the composer had to delete all the posts about the song from his social media accounts.

British band Coldplay was joined on stage by exiled actress Golshifteh Farahani to sing “Baraye…” in a Buenos Aires concert.

Art as a record keeper of history

Protest art also helps preserve important lessons of history by capturing the emotions felt by the protesting people for posterity with artists becoming the unofficial record keepers.

As arts develop along with the evolving protests, we rarely appreciate the important role it plays in fostering public support, unifying societies and ensuring the momentum of protests remains alive. It is only in hindsight after protests achieve the desired outcome that we look and appreciate the role of arts in protests. Protest arts are important as they help us retain the important lessons needed in future fights against human injustice.

Song: Shervin Hajipour – Baraye